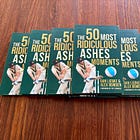

You may have heard that I’ve got a new book coming out, co-written with Alex Bowden. It’s The 50 Most Ridiculous Ashes Moments. In it, we count down - and you’re probably unable to crack this from the enigmatic title - the fifty most ridiculous Ashes moments (albeit with the genuinely obscure caveat: ‘of the past 50 years’). But, hey, perhaps that’s not enough for you. Fine. To sweeten the deal, Alex and I have written a piece apiece on the 52nd and 51st most ridiculous Ashes moments, just for our online readers (that’s you!) to online read.

I’ve got number 52 here - the moment when Mark Waugh replaced Steve in the Australian Test side during the 1990/91 Ashes. Alex will provide the number 51 moment when he’s good and ready.

Either way, please pre-order the book! Pre-ordering is good and proper and helps authors in ways you can’t begin to imagine. Plus, you’d feel like an absolute fool if you were left stranded 52 or 51 moments away from the top ridiculous moments in the list.

Twins are more likely to be similar than just about any other randomly chosen pair of people in the world. Identical twins share DNA, obviously, which everybody agrees is a massive head start when it comes to similaritude (‘oh, you’re a physical clone of me? Yes, that does render us quite comparable’). But even with fraternal twins, you’re still looking at duos typically raised in the same family, sharing bedrooms and birthday parties and underwear and dentist appointments and whatever else twins share as they grow up. So, even if, genetically speaking, they’re mere siblings, their shared environmental upbringing gives them a similarity boost denied to more womb-hogging brothers and sisters.

But this self-evident fact doesn’t exactly stir the soul, does it? No, it’s far more interesting to think about twins in terms of their differences. The good twin vs the evil twin. The analytical twin vs the emotional twin. The desert planet farmboy twin vs the Imperial Senate diplomat twin. The musclebound twin vs the DeVito twin. The twin who can usefully turn into any form of animal vs the twin who can less usefully turn into any form of water1.

And, of course, when it came to the 1990/91 Ashes, the twin who was in the Australian Test cricket side vs the twin who wasn’t.

Up until that 1990/91 series, and for the first three Tests of it, the designated twin in the Australian Test cricket side was Steve Waugh. Steve was a dashing all-rounder who made his Test and ODI debuts at age twenty as part of the Australian selectors’ desperate quest to find somebody - anybody - who might be willing to stick around and give Allan Border the occasional hand during the ongoing thrashings of the 1980s.

Steve did, indeed, stick around during those first few years, contributing just enough runs and wickets to retain his spot, given the dearth of alternatives. In the 1986/87 Ashes, for example, he averaged 44.28 with the bat, including a trio of seventies, and took ten wickets at 33.60. Good all-round effort. Worth persevering with.

Alas, Steve’s efforts weren’t enough to prevent the home side from losing that series 2-1, as England comfortably retained the Ashes they’d won in 1985. (Australia’s lone win was the dead rubber, a match most famous for Peter Taylor’s debut - see Entry [redacted], The Who’s ‘Who?’ of Ashes Cricket). Indeed, England had won five of the last six2 Ashes series, and it was not unreasonable for their fans to believe that the urn may remain at a similar standstill for the foreseeable future.

Which, of course, it did. But not in the way they had hoped.

Because, as we’ll see in Entry [redacted] (Waugh Stars), the 1989 series saw the Australian selectors’ faith in Steve Waugh finally pay off, when, 27 Tests into his career, he made his first Test century. Then another one. Both undefeated, on his way to 506 series runs at the ridiculous, Bradmanesque average of 126.50. Australia won the series 4-0, and ended the decade in possession of the Ashes.

Unfortunately for Steve, he began the next decade dreadfully. In his first six Tests of the 1990s, against Pakistan, New Zealand and England, he scored a total of 114 runs at an average of 14.25, with a top score of just 25. Even more unfortunately, Australia had become a sufficiently good team with sufficiently strong reserves that poor runs of form could no longer be overlooked. There were good batters waiting in the wings for their Test opportunities.

At the apex of unfortunateliness for Steve Waugh, the next good batter waiting in the wings for a Test opportunity was his twin, Mark, who had been Sheffield Shield player of the year in 1987/88 and 1989/90, and a regular in the Australian ODI side since the summer of 1988/89. In his autobiography, Steve recapped an absurd piece of sketch comedy in which he visited the family home (the Waugh Zone, as they almost certainly didn’t call it) to tell his parents he’d been dropped from the Test side and answered the question of ‘who’s your replacement?’ by pointing to Mark and saying ‘He’s over there. Congratulations - you’re in the Test side.’

The new twin in the Australian Test side differentiated himself from his predecessor by scoring a century at his very first attempt in the fourth Test in Adelaide. Coming in at 4/104, which soon became 5/124, Mark scored 138 to help Australia recover to 386 all out. The innings itself unfurled straight from a Mark Waugh innings generator - all effortless timing and nonchalant gap-finding, striking 18 fours (compared to the twelve in total from everybody else).

The Test was eventually drawn, but Mark’s innings was dazzling enough to reinforce casual fans’ opinions of what they’d been telling everybody all along - that Mark was the twin who belonged in the Test side.

Selectors agreed, and for a significantly longer period of time than might seem rational in hindsight, not a single person seemed to ever seriously consider the idea that ‘maybe - and I’m just throwing it out there - they’re both half-decent cricketers, right? Could we perhaps consider having both twins in the side?’

Oh, sure. During an overseas West Indies tour in April 1991, Steve replaced Greg Matthews for a couple of Tests, batting at a startling seven. But he only scored 26, 2 and 4*, before being replaced in turn by Peter Taylor. The selectors’ policy seemed justified. One Waugh only in the team, please. Highlander rules apply.

Did Steve consider beheading his twin brother? To his eternal credit, he did not. Instead, he went away and rebuilt his game. He left the dashing, pleasing-to-the-eye caper to Mark and instead reimagined himself as a gritty, don’t-give-a-fuck-how-I-appear-to-the-eye batter. Sufficiently differentiated, Steve returned to the side eighteen months later. Again, he found himself in a somewhat startling batting position. This time, at three, the sole free spot after David Boon had moved to the top of the order to replace Geoff Marsh, sacked the summer before3.

Steve’s return to the side stuck this time, thanks primarily to a century in the third Test that was otherwise completely overshadowed by the extravagant parasol of Brian Lara’s 277.

By the time the 1993 Ashes rolled around, five months later, Steve had abseiled his way back down the batting order to six, a couple of spots below Mark at four. Two twins in the Australian Test side? Could it possibly work?

Yes. Of course it could. Over the course of that 4-1 series victory, Mark amassed 550 runs at 61.11, Steve 416 at 83.20.

It was a series that laid the foundation for the selectors to completely abandon their previous policy. Instead, the twins took up a slot apiece in the side for the better part of a decade, on the way to a total of 108 Tests together. This tally included 26 Ashes Tests (win-loss record: 17W, 5L, 4D) together over five series (5W, 0L, 0D). Much like viewers of the Highlander sequels, England cricket was left wondering what, exactly, is so bloody difficult about sticking to a very simple, very clearcut rule that ‘there can be only one’.

PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY OF THE 50 MOST RIDICULOUS ASHES MOMENTS VIA https://liebcricket.com/ridiculousashes/

If you’re unaware of Zan and Jayna, the Wonder Twins of the late 70s/early 80s Super Friends cartoon show, then, hoo boy, does Wikipedia hold some wonders for you. Spoiler: ‘The pair also have a pet monkey, Gleek, who assists in their crime-fighting activities.’ Come on, now.

Although, as always, whenever somebody mentions a stat in this form, you know it equally accurately means five of the last seven series.

Fun fact: Marsh’s sacking was announced before the start of play on the final day of the fourth Test against India, and saw captain Allan Border refuse to take the field for twenty minutes, preferring instead to get on the phone to deliver a tirade to the chairman of selectors for this decision. Great stuff.